Dear E,

I read his book last night, before restart. I read all of the books in my room. I will ask him today if I can read the rest of the books in the house. Maybe after that I’ll be able to help him with his new book.

Marta read webzines on her palmpilot. She did that every morning over coffee. There were no other books in her house except for books of pictures for the gallery. The people in the block of flats mostly did the same. I’ve never come across so many print hardcopy books in all my life. They’re heavier to handle, and you have to be careful with their pages, but I really enjoy it. Alone with all those books! In my own room! I’m very very lucky, I think.

I hope things are good with you as well.

I hope that very much.

*

He was sitting there waiting when I came into the study this morning. His place is behind the desk, a big bare desk, with many sets of shelves behind it.

I sit to one side, on a high-backed chair, since I have no need of a desk: only access to a powerport and a data projector.

“So what did you think?”

“I don’t understand, sir.”

“What did you think of my book? You read it, didn’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Was it interesting?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You understood it all?”

“I don’t know. I think so, yes.”

“Well, do you think it’s any good?”

“I was happy to be able to read it. I would like to read other books as well.”

“You mean other books on the same subject, to check up on me?”

“Any other books.”

“You’re not going to praise it, are you?”

“I don’t understand.”

“I just want to get an opinion out of you: it was too long, too dense, dull, amusing, under-edited, beautifully proportioned …”

“But … I am a clan. It is my job to help you with your book, record your ideas, read back passages for you to correct …”

“That doesn’t mean you don’t have ideas of your own, surely?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What are they?”

“I am … confused by your question.”

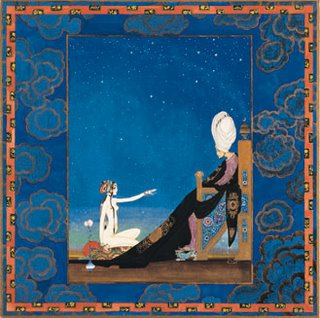

“Look, the book is about Shahrazad and Shahryar, isn’t it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“What is their story?”

“Verily the works and words of those gone before us have become instances and examples to men of our modern day, that folk may view what admonishing chances befell other folk and may therefrom take warning; and that they may peruse the annals of antique peoples and all that hath betided them, and be thereby ruled and restrained. Praise, therefore, be to Him who hath made the histories of the past an admonition unto the present! Now of such instances are the tales called 'A Thousand Nights and a Night,' together with their far-famed legends and wonders. Therein it is related …”

“No, no: what is the essence of their story? She tells him stories to stop him cutting off her head: for 1001 nights she fights for her life with stories … And why does he want to kill her?"

“The king believes that all women are unfaithful to their husbands, so he must execute each new wife before she gets the chance to betray him.”

“And why does he think that?”

“Because his own wife betrayed him with a slave, his brother’s wife betrayed him with a cook, and the virgin abducted by the ogre has betrayed him 150 times …”

“Precisely. And is the king correct?”

“I … do not know.”

“Are all women unfaithful to their husbands?”

“It seems unlikely. Many husbands are unfaithful to their wives.”

“Are you speaking from experience?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Ah. So you don’t agree with Shahryar?”

“No, sir.”

“You don’t think he’s right to kill a different girl every morning?”

“No, sir.”

“So you’re on Shahrazad’s side?”

“Yes, sir.”

“You would tell the ogre stories every night in order to stop him killing you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Is that how you see me? An ogre you have to placate with conversation and stories?”

“No, sir.”

“But you know that I killed my wife. You do know that, don’t you?”

“No, sir.”

“But you must have been told! Somebody must have mentioned it to you. It’s common knowledge, after all. You were at the booklaunch …”

“Yes, sir.”

“Then you heard what they said, those women who assaulted me? They called me a murderer. That’s why they threw the glass.”

“I … did not understand what they said.”

“But you understand it now, don’t you?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Well, don’t you have any questions for me? Anything you’d like to clear up?”

“No, sir.”

“Aren’t you afraid? If I’ve killed one woman, I might kill two. Doesn’t that make you scared of me?”

“No, sir. You are my master.”

“I am your master. Does that give me the right to kill you, then?”

“Yes, sir.”

“'Yes, sir.' I can kill you if I want to!”

“Yes, sir. You know that. You know that legally a human may dispose of a clan. It would be treated as a breach of your service contract, and you would have to pay a fine to the company or give reasonable cause within thirty days of the action …”

“The action. The murder, you mean.”

“No, sir. It has been legally determined that such an act cannot be construed as murder, only as damage to property.”

“So I can kill you and wrap you in plastic and throw you away, and the only consequence to me will be that I have to write a letter of explanation within thirty days?”

“Yes, sir. You know all that. The company representative must have explained it to you.”

“It didn’t sound the same coming from him. Doesn’t it worry you at all?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you want me to kill you?”

“No, sir.”

“So you’re trying to stay alive, in other words?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’m the brutal, mad king, with blood on his hands, and you’re the beautiful young wife?”

“No, sir.”

“No?”

“I am not your wife, sir.”

“No, no, that’s right. I had a wife. She was the one I killed, not you. You’re just the one who makes me breakfast and is fond of kittens.”

“Yes, sir.”

“So you see why I want your opinion on my book? Who else is better placed to comment on it?”

“I … don’t understand, sir.”

“No, I suppose you don’t. Maybe someday I’ll tell you about my wife. I doubt it, though. They all said it wasn’t my fault. But I’m not so sure. Those women at the launch didn’t think so, and they probably have a point. If it wasn’t my fault, whose was it? They told me not to dwell on it, either – to try and dismiss it from my mind, get on with other things. That’s why you’re here, actually – to help with my work, to distract me from thinking about the past …”

*

My master is sometimes quite difficult to talk to. Some of the questions he asks he answers himself. Others he wishes me to answer. I have to try to distinguish between them by timing how long he waits after raising his voice interrogatively. Sometimes it is as long as four or five heartbeats before he goes on again. I have to be careful not to interrupt, as it might break his train of thought.

I am recording everything he says to me, in case any of it is needed later for his book.

Perhaps this is his normal way of refining his thoughts.

*

He has given me permission to do more reading. Anything in the house except for the books in his study. I think that he likes me to read. Once the housework is done, there are few other duties.

He will not let me bathe him or dress him. He eats very little, and spends all his evenings alone. I think that he drinks alcohol then, as I can smell it in the room after he goes to bed.

Some of my other masters drank alcohol, too.

Love

your sister, Eva

It is funny to sign my posts with “love.” It is an intimate formula which I selected from my letter template, but now that he has explained to me about my little kitten, I wonder if I can use it to you anymore? After all, we have never met. And yet I know you as I know myself. What other word can I employ?

No comments:

Post a Comment